6. Challenges

During the development and deployment phases of Tumbleweed, our team faced several technical challenges regarding consumer data consumption, pipeline auto-deployment, Tumbleweed component configuration, database management, and application security.

6.1 Consumer Service Data Consumption

Although Debezium maintains a source connector which is a good fit for Tumbleweeds use case, it does not provide an appropriate sink connector for microservices on the consumer end. Without a sink connector built into Tumbleweed, anyone who wished to integrate our pipeline into their architecture would be required to extensively alter their consumer codebases, greatly increasing the level of user complexity. They would also be required to find a Kafka client which matched the language of their codebase, before they could even implement message consumption. In addition, the consumer would also have to implement error handling and more complex message processing. Finally, this would require public access to the Kafka cluster containers which would be an increased security risk.

It seemed logical for Tumbleweed to create a custom sink connector for our pipeline. After researching, we found KafkaJS, a Node.JS Kafka client. This allowed us to integrate Kafka communication into our architecture. KafkaJS was used to create the connection between Kafka and the consumers, monitoring topics specified by the user and streaming incoming messages to a provided Tumbleweed endpoint via Server Sent Events (SSE).

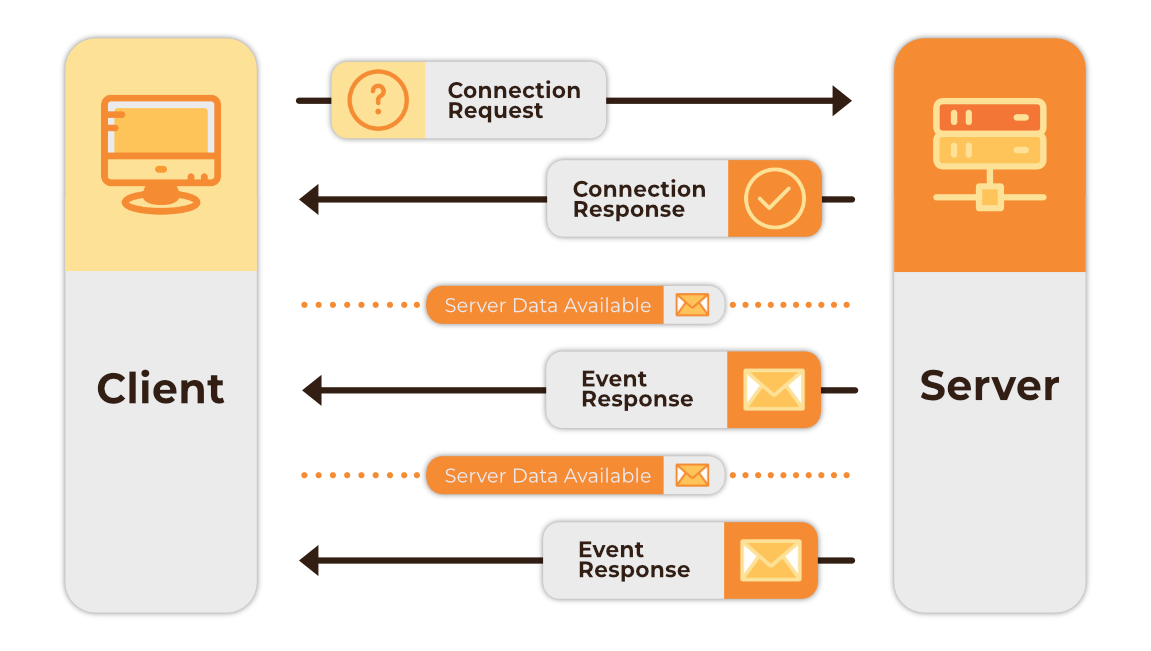

SSE creates a unidirectional long-lived HTTP connection from server to client, allowing us to push messages to consumers in real time, which is ideal for the goals of our application. In order for a consumer service to receive these messages, only a small amount of code is required in their codebase, and this can be written in any language that supports SSE.

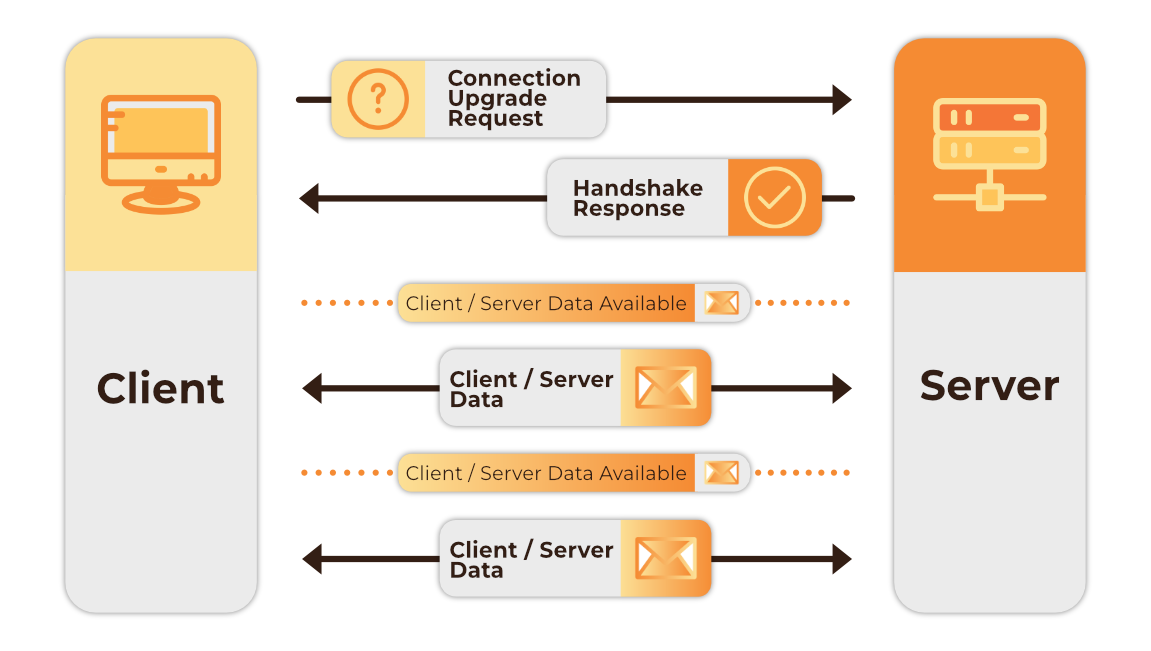

Two other options we explored were the use of websockets or polling. Websockets are a communication protocol that allow for real-time, bi-directional communication between a client and a server. The connection between client and server is persistent; once the connection is established, data can be transmitted between the client and server in real time. While the real-time communication capabilities of websockets suited our needs, we did not need bi-directional communication.

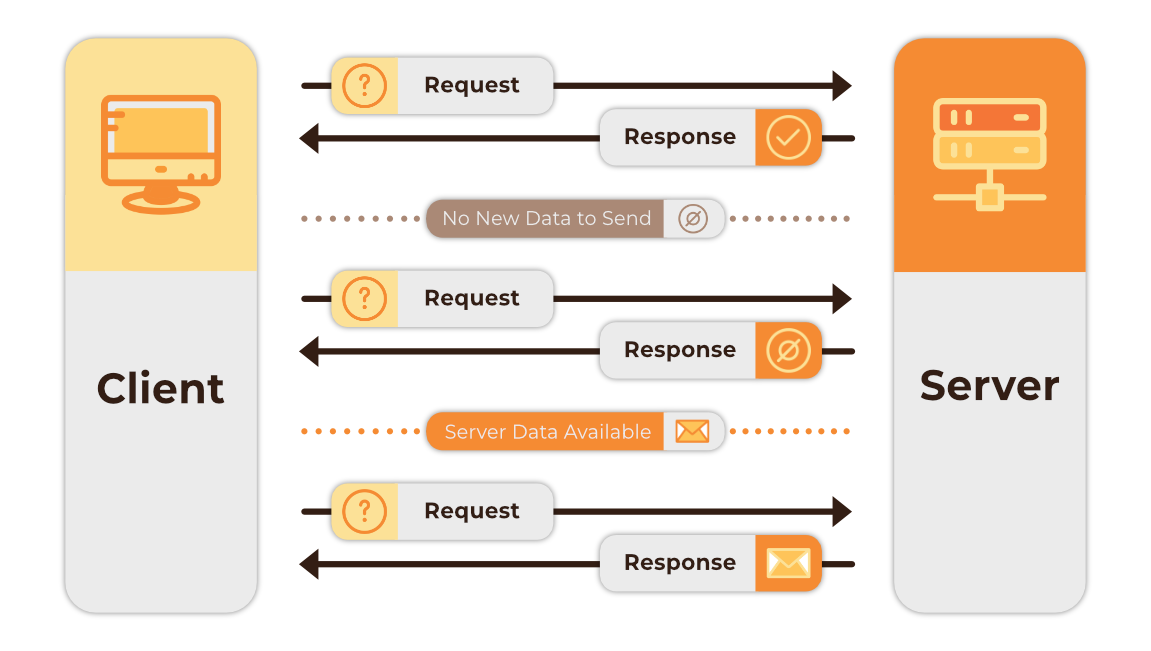

Polling is another method that can be used for real-time communication between servers and clients. There are two different types of polling – short and long. Short polling involves a client repeatedly sending HTTP requests in regular intervals to the server to check for new data. The advantage to using short polling is that it’s simple to implement on both the client and server side, and is ideal for requests that take a long time to execute, as it allows for asynchronous processing. The drawbacks are that short polling can result in excessive network requests, leading to increased server loads and network traffic. Additionally, updated data is only received during the polling intervals; the user does not receive their data as quickly as compared to other solutions.

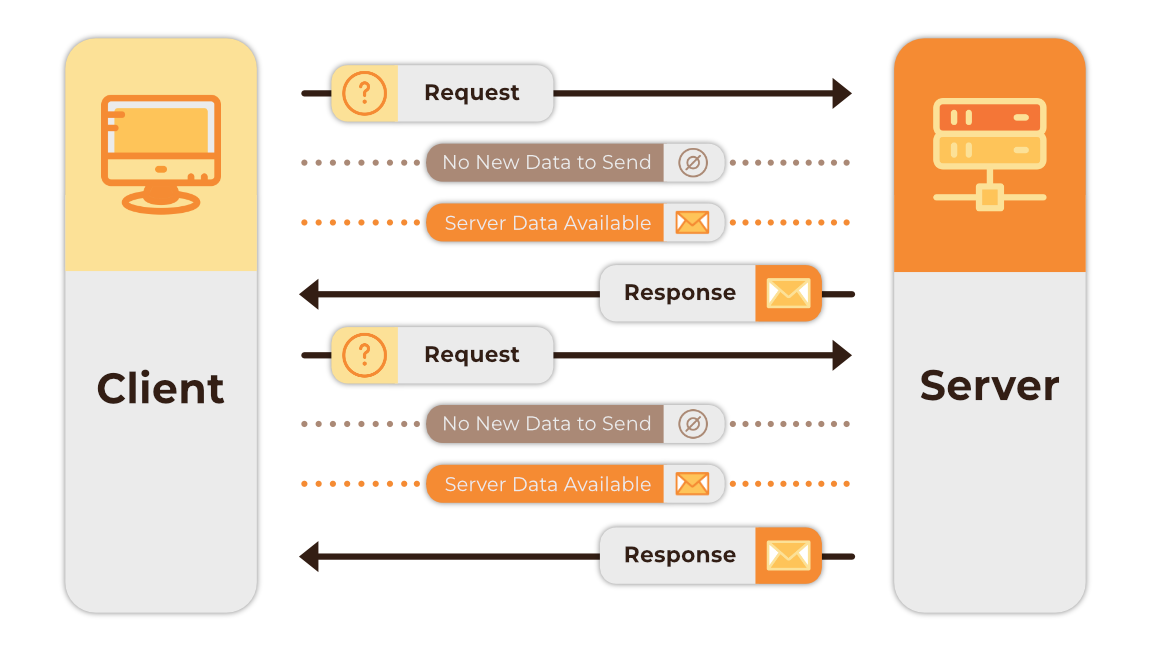

Long polling differs from short polling in that it keeps the connection open until new data arrives. Once the client receives the response/data, a new request is sent either immediately, or after a predetermined interval to establish a new connection. The advantage again lies in its simple implementation. However, reliable message ordering is not guaranteed due to the possibility of multiple HTTP requests from the same client to be in flight simultaneously 1. There is also higher latency due to the need to reopen connections, and the client having to wait for a server response. Finally, both forms of polling may face rate limiting issues if trying to receive the high volume of frequent responses which Tumbleweed would need to handle.

6.2 Terraform Deployment with Multi-Node Kafka Cluster

When writing the configuration files for Terraform and deploying the Tumbleweed infrastructure, we ran into issues with the Kafka brokers, Kafka controllers, Connect and the Tumbleweed backend API not being able to communicate with each other. This miscommunication resulted in the services not being able to reach a stable running state.

In the early versions and development stages of Tumbleweed, we used Docker to run our Kafka containers, and for the most part, inter-container communication was abstracted away from us, due to the fact it was running on our local machines and using Docker's default networking settings. Transitioning to ECS deployment introduced new challenges in enabling containers to communicate securely, while also restricting external access to services that did not need to be publicly exposed.

To resolve these issues, we used Amazon ECS Service Discovery to provide DNS hostnames for each of our services, allowing simplified service-to-service communication in our ECS cluster. We also utilized a VPC (Virtual Private Cloud), a NAT (Network Address Translation), an Internet Gateway, security groups and routing tables to manage internal and external communication.

6.3 Multiple Pipelines Sharing a Single Replication Slot in Development

A replication slot is a feature in Postgres that provides a robust way to handle data replication between a primary database server and one or more consumers, such as secondary Postgres servers, CDC tools, or other downstream systems 2. These replication slots ensure that no data is lost by keeping necessary WAL (Write-Ahead Log) files until all consumers have confirmed they have received that data 3. We can minimize performance impact on the database while maintaining consistent data change order by reading from the WAL instead of querying the database directly.

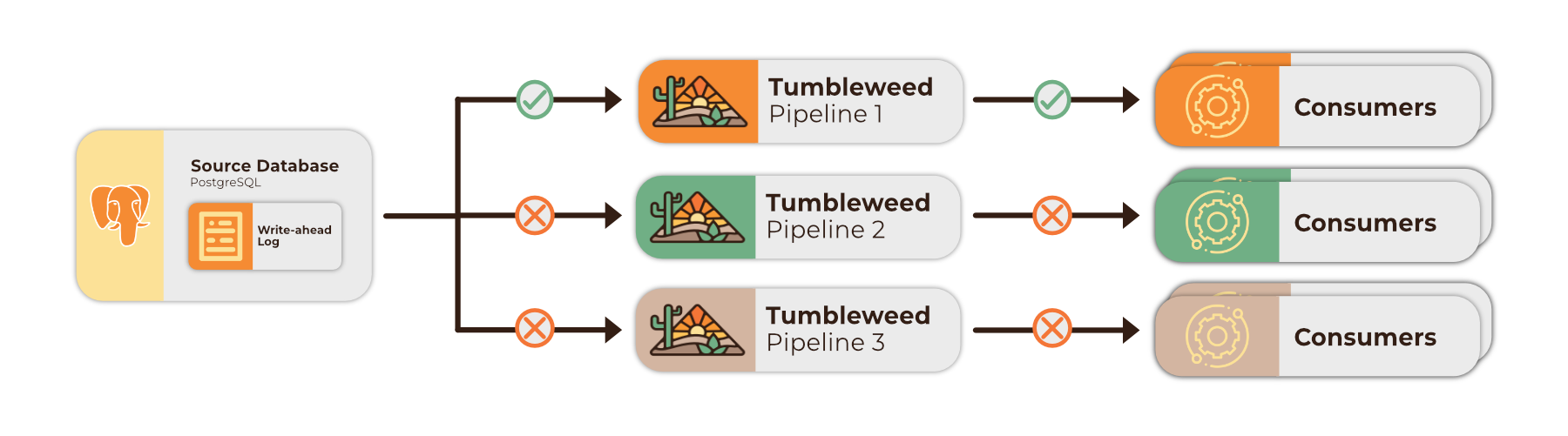

The production version of Tumbleweed is meant to be run as a single pipeline instance for a full architecture of services, with a single source connector for each producer service. During the early development stages of Tumbleweed, each member of our team had their own instance of Tumbleweed running, but these individual instances shared the same replication slot on the same AWS RDS source database.

A PostgreSQL replication slot will only emit changes once 4. If those changes are captured by a single pipeline, they can be later streamed to any number of downstream consumers. However, as our team was running multiple pipeline instances, these changes were only captured by a single instance, and therefore only the consumers of that instance would receive data.

The solution to this issue in development was to create a unique replication slot name for each connector. This replication slot name was based on the connector details that the user provides when creating a new source. In doing so, we were able to ensure that each developer was able to connect to the same source database for testing, and still consume the data.

While this issue was related to development of Tumbleweed, it should not arise in production. However, to make sure that such a scenario cannot be introduced unintentionally, the production version allows for only a single uniquely-named replication slot per source connector.

6.4 Managing WAL Disk Size Growth in PostgreSQL on AWS RDS

When a replication consumer goes offline, its PostgreSQL replication slot becomes inactive. When this occurs, Postgres will retain all WAL segments after the latest LSN (log sequence number) for unconsumed changes. The LSN is an unsigned 64-bit integer used to determine a position in the WAL 2. These segments are small, 16MB by default, but can be configured to larger sizes. Tumbleweed needs to retain WAL segments as it uses Debezium, which relies on the WAL to capture changes. If a consumer goes offline and the WAL segments are not retained, changes made while the consumer is offline will be lost.

During development, we used AWS RDS to spin up a Postgres database to test database connectors and data consumption, and we encountered a challenge with uncontrolled growth in WAL disk size. RDS writes to a heartbeat table in the internal “rdsadmin” database every 5 minutes. Even when the database appears to be idle, this generates traffic. Additionally, in AWS, RDS has increased WAL segments from 16MB to 64MB in size 5. Thus these periodic writes to the heartbeat table within the “rdsadmin” database trigger a new WAL segment of 64MB to be created. If the replication slot remains inactive and the LSN doesn't advance, Postgres will continue to retain these segments. This causes the quick consumption of disk space, potentially causing the database to crash.

We explored several solutions to address this issue:

Monitoring and removing inactive slots

The first solution was to manually remove any Debezium connectors that were no longer being used along with its replication slot from the source database. While this solution was effective, it required frequent monitoring of RDS disk usage and replication slot activity. This was prone to human error, occasionally allowing WAL growth to spiral out of control.

Creating and writing to a heartbeat table

Our second solution was to create a heartbeat table in the source database and have Debezium write to it in five-minute intervals, keeping the database and its replication slots active. This kept replication slots active, and prevented WAL segments from accumulating.

Removing the inactive slot on connector deletion

The third and final solution was to create the heartbeat table as in the second solution above, while also removing replication slots when its connector to the source database is removed. This seemed to be the optimal solution as it does not require frequent monitoring of the WAL size. It also ensures the WAL remains at a consistent size, between 100MB to 200MB.

While this solution controlled the growth of the WAL disk size, we recognize that this may not be an issue in production. The source databases users will be providing will more than likely be in a continuously active state, i.e., data being written and messages being consumed frequently. However, in the event that this was not the case or for pre-production testing of a user's services with a Tumbleweed pipeline, we aimed to provide a solution that prevented the WAL disk size from growing out of control and crashing their database.

6.5 Securing Tumbleweed

Security is important when building an application that manages and interacts with a user’s data. Tumbleweed is self-hosted and auto-deployed to AWS ECS on the user’s AWS account. Each user spins up their own instance of Tumbleweed which is accessed via a public IP provided by ECS.

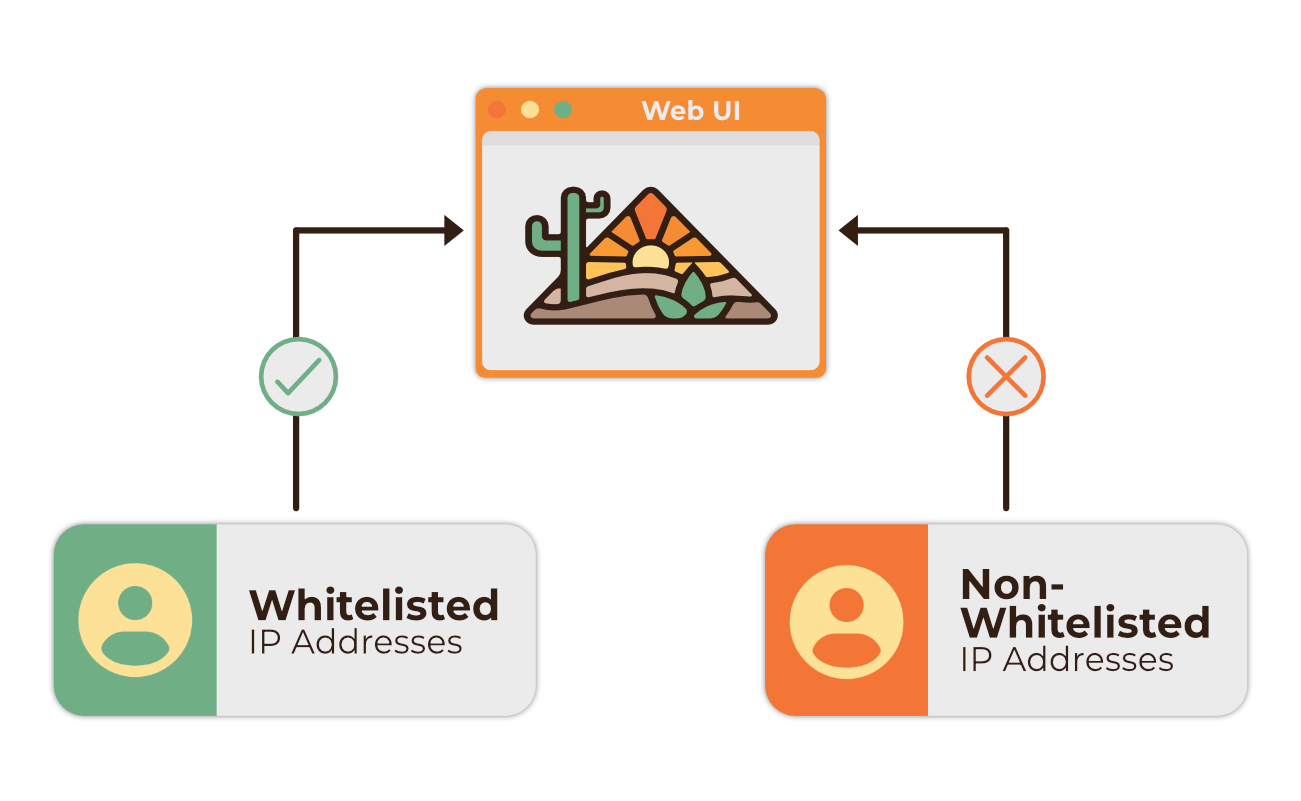

This deployment model introduced security challenges. Because the users access Tumbleweed through a public IP address, our primary focus was on preventing unauthorized access to the pipeline’s data and infrastructure. Securing Tumbleweed required implementing robust measures to protect communication channels, and control access through whitelisted IPs, IAM roles and policies.

Whitelisting IPs for Controlled Access to Pipeline UI

During Tumbleweed’s installation, the user is prompted to provide a list of IP addresses to whitelist. These IP addresses are stored in a Terraform variable, which is then used to configure an ECS security group, granting controlled access to the application. This is done through creating inbound rules that allow traffic only from the specified IP addresses. By doing this, we ensure that access to the application is tightly controlled and limited to trusted resources.

While this does secure the application, the tradeoff of this design is that the user must find out the IP address for each machine that intends on accessing the application’s UI. This process can be tedious, especially in environments where the public IP address is not readily available.

Additionally, Tumbleweed currently lacks the ability to alter the whitelist after deployment without complete teardown and redeployment. This means that users are essentially stuck with the IP address input at deploy time which can become burdensome over time, particularly for users with a large number of machines or for those operating in cloud environments where instances are frequently spun up and down. While whitelisting provides robust security, it may not be the most user-friendly approach for all scenarios.

Controlling Access Through Security Groups

For public access control, public facing Tumbleweed Backend API ports were routed through the Internet Gateway, with access being controlled by specific security group ingress rules. For private access control, outgoing traffic from Connect and Debezium in our private subnet was routed through the NAT gateway, allowing contact from that service to user source databases but isolating it from other uninitiated direct internet access. Inter-service communication was made possible by placing the services within a VPC, with its security group having unrestricted ingress rules for a private CIDR block. In doing so, we were able to prevent direct internet access to the containers which do not require such access.

Footnotes

-

K. Kilbride-Singh, “Long Polling vs WebSockets - which to use in 2024,” Ably Realtime, Dec. 21, 2023. ↩

-

“Replication slot in Postgres - Ladynobug - Medium,” Medium, Jan. 04, 2022 ↩ ↩2

-

“What are PostgreSQL replication slots and how do they work?,” DragonflyDB. ↩

-

“47.2. Logical decoding concepts,” PostgreSQL Documentation, Nov. 21, 2024 ↩

-

G. Morling, “The insatiable postgres replication slot,” Gunnar Morling Blog, Nov. 30, 2022. ↩